How You Fail Is More Important Than If You Fail

The thing we’d been waiting for just dropped from the sky into our laps.

A message flashed up on my mobile from a friend I hadn’t heard from in a while.

“Hey,” he wrote, “Would you guys be interested in a cheap car? It’s a camper van.”

I couldn’t believe it. For months my husband Manel and I had been searching for a camper van – something small, like a VW Eurovan – so we could more easily take off to the mountains on the weekends.

When Manel got home, I excitedly filled him in. Our friend needed to sell the van right away. He’d give it to us half price, a real bargain.

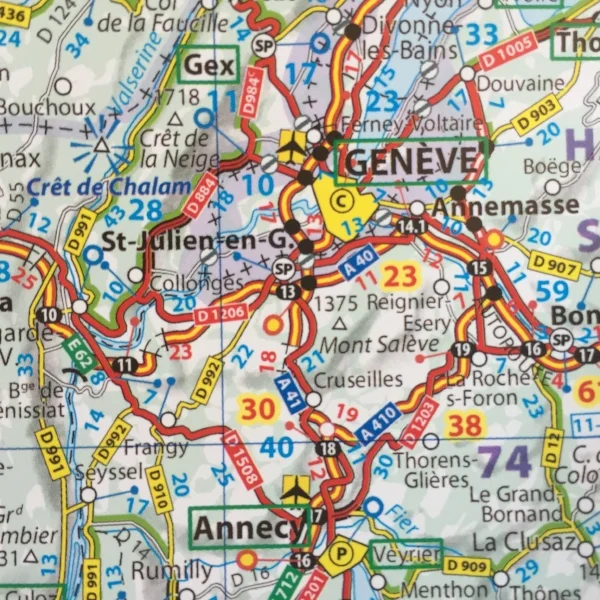

The only catch was that the van was parked in Geneva. We’d have to go pick it up.

Manel couldn’t get away for a whole weekend, but I could.

We calculated the risk.

Best case scenario: We’d get a great deal on a camper van. We would finally have a camper van. We’d been talking about buying a van since January and we’d been seriously terrible about making a decision on it.

Worst case scenario: The van would break down. This seemed unlikely. Our friend said we could pay for it once we safely got it back to Spain.

I booked a one-way ticket to Geneva.

This was exactly my sort of adventure. I was thrilled. I tried to find a friend to come with me, but it was short notice. In the end, I went alone.

I was so excited. I’d never been to Geneva or seen the Alps (except from an airplane). I’d love this road trip home through France, even if I was just passing quickly through.

Then, less than 24 hours after my arrival in Geneva, I found myself at a rest area alongside a freeway in France, trying to figure out how to call a tow truck.

It was surreal. The worst case scenario came true.

Another 24 hours later I was in the airport in Lyon, waiting for a flight back to Barcelona.

Disappointed, but relieved to be headed safely home.

There was just one last thing on my mind. The night before, Manel had asked me, “Hey, are you going to put something on Facebook?”

Ugh.

At the start of my trip, I’d posted a photo on Instagram and Facebook about my adventure. I’d hoped to keep sending photos all along the road. It would be fun to share with others.

Now I regretted it. I felt a flash of annoyance at Manel for reminding me that I should say something publically about my misadventure.

“I don’t want to,” I confessed. “It feels like a big failure.”

“It’s not,” he said. “You tried something. It didn’t work out. You learned something. That’s all you have to say. It happens to everybody.”

I knew he was right.

At least for his sake, I needed to put something up. Otherwise everyone back home would keep asking him about our new camper.

So as I waited in Lyon, I posted a photo and said I was coming home, without the van.

When Manel picked me up in Barcelona, I was happy to tell him I’d done it.

Word was out. We could move on.

Sometimes the worst does happen

The thing is, we don’t always have control over whether something we take on will be a success or failure.

Sometimes we do our best, and it’s not enough. Life throws a curve ball.

We don’t have control over the results. Yet we do have control over who we are and how we act if, and when, the ship goes down.

And yes, there is always something to learn.

After a few days back in the safety and peace of home, I could see that more clearly.

You win some, you lose some, I was able to say.

Also, I was starting to feel a growing appreciation for being able to handle the whole thing calmly, alone, and in a foreign country.

I had driven that van really well, right up to the moment it died.

That meant a lot to me because back in December of last year I’d started the process of getting my Spanish driver’s license. Spain and the U.S. don’t have a reciprocity agreement with drivers’ licenses. So even though I had driven for 20 years, I had to start completely over and enroll in Spanish driving school.

I was furious, then dumbfounded, when – even by devoting two to three nights a week to study in the driving school’s computer lab – it took me until late March to pass my written test.

Then it took me another six weeks to pass my driving test.

People congratulated me on getting my license so fast. It was rare that someone would pass both tests on their first try; most people take at least a year to get their driver’s license.

When my instructor told me I’d passed, I could have fallen on the ground in relief.

This truly had been the stupidest, most agonizing bureaucratic hoop I’d ever had to jump through, I thought.

I’d had to do it (regardless of what I thought) because there was no other legal way for me to drive in Spain – and by extension, the E.U.

It had taken sheer willpower.

Now I could see how the experience had helped me. As an American, what Spanish driving school essentially taught me was how to drive a stick-shift through very small, narrow (and often medieval) spaces.

I’d squeezed my camper van in and out of the tiniest parking spots without tearing off any mirrors. I parallel parked it. I flowed gracefully in and out crowded roundabouts.

They’d never guess I was American!

I hadn’t cut anybody off. I hadn’t entered the wrong way. I hadn’t run any red lights. I filled up with diesel, not gasoline. No one honked indignantly at me (until the thing started spewing smoke in the French countryside).

If I still lived back in Portland, Oregon, this adventure would have been the equivalent of buying a car off Craigslist in Boise and driving it home. No big deal.

But I hadn’t gone to Boise. I’d gone to Geneva.

This was really a top-notch failure for me. I’d come a long way to even give it a shot.

Being forced to stop along that stretch of French highway gave me a real chance to notice that.

Now it was time to set off again.